New York's Dance of Displacement

Reprinted from Lincoln Center’s SJH Microsite, where Black & Boricua culture thrived before displacing 7K residents to build NYC’s iconic arts hub. Listen to my playlist of 100 musical years there.

At the turn of the last century, the Manhattan neighborhood of San Juan Hill, or "Black Bohemia" as residents knew it, was a thriving hub of musical innovation among Blacks and Latinos. It was a place where politics and poetry danced as easily as artists and advocates met to jam and blaze new ground.

A lost slice of New York City life, San Juan Hill, according to maps, ran along fourteen West Side Story streets centered near 62nd and Amsterdam Avenue. Blocks extended from 55th to 69th Street and beyond, parallel to Central Park on what was once the unmapped native land of the Lenape people.

Back then, New York City bustled with working-class migrant and immigrant communities, none with more creative energy than the one that called the streets of San Juan Hill home. Yet, the area remained an enigma.

In spite of the many juke joints, basement bars, restaurants, and clubs, who would've thought San Juan Hill would be the arena for the musical battles between bebop and mambo? Yet the area remained a mystery, a conundrum of Black and Puerto Rican migrants who worked, lived, and played together in a creative community of shared roots, routes, and rhythms.

The early music reflected an agricultural nostalgia of political displacement wrapped around working-class struggles. Gradually, San Juan Hill became the nexus to better gigs, and better living conditions for Puerto Ricans crowded into politically charged East Harlem. While the up-tempo, polyrhythmic beats of Latin music were recorded in New York at the start of the 20th century, the history of those musical diasporas remains largely untold. Digging through newspapers, theater programs, and literary magazines from those early years reveals the politics under which San Juan Hill's growth and upheaval helped influence Latin and jazz music in New York.

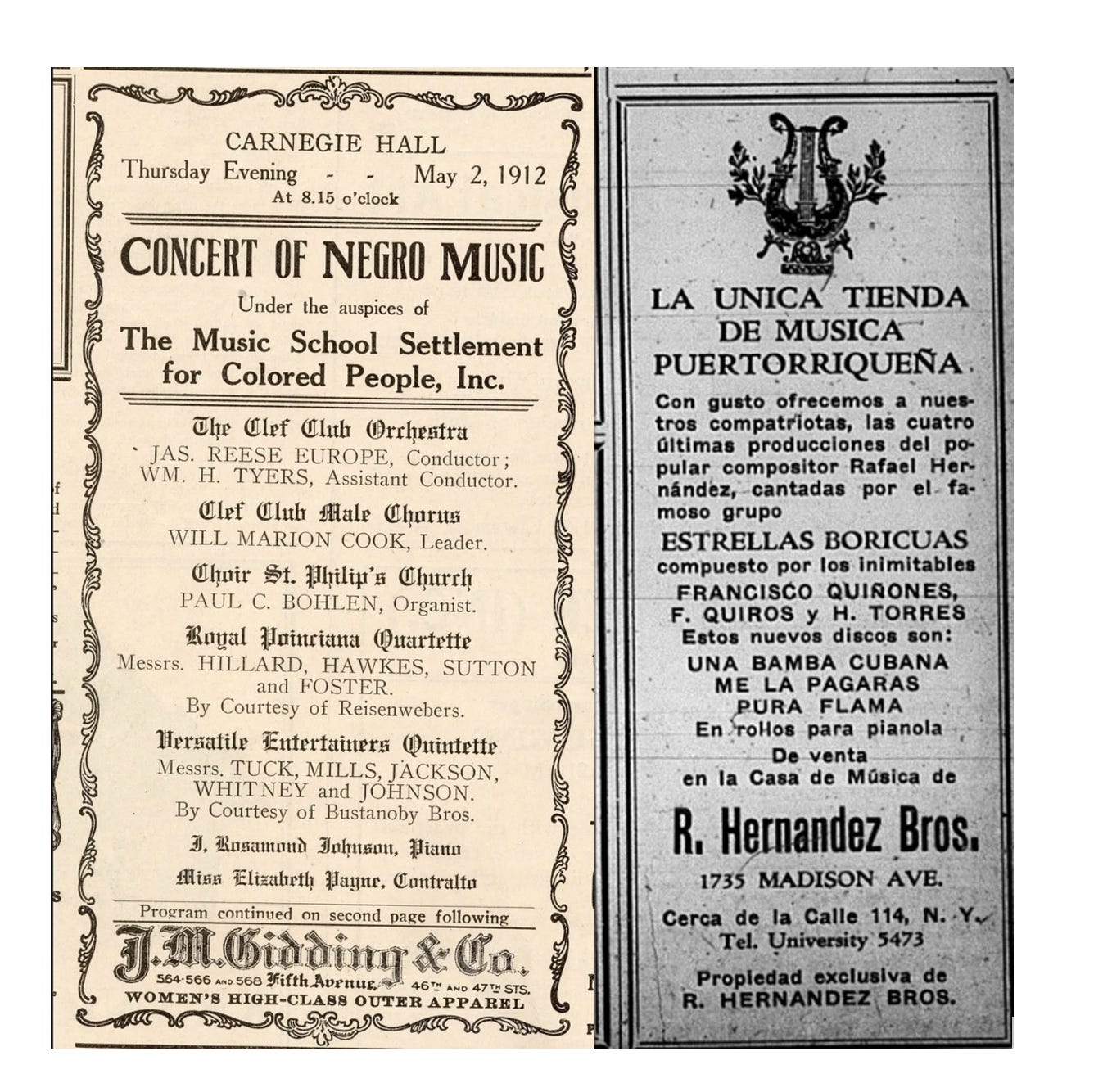

While bandleader James Reese Europe broke racial barriers advocating for Black musicians on Broadway’s 53rd Street with his Clef Club, the noted Afro-Boricua historian Arturo Alfonso Schomburg dug up his roots from his San Juan Hill home after campaigning for the independence of his native Puerto Rico from Spain. Both displaced migrants, they blazed new trails redefining and rediscovering the role and history of Black and Boricua people in America.

After one hundred years, the city is unrecognizable from what it was during San Juan Hill’s heady days. Affordable housing today is as hard to find as a public phone booth. Many residents have been displaced and neighborhoods lost due to financially driven development, and San Juan Hill is one such example. New York City's disrespected working-class communities have been the casualties of its financial future, as has the artistry that thrived there. The music left behind continues to mark the footprints of the creations and collaborations forged in San Juan Hill and other city neighborhoods.

A cautionary tale for all of Gotham’s creative, working-class communities, let’s take a deeper dive into “Black Bohemia.”

The music played

While bandleader James Reese Europe1 broke racial barriers advocating for Black musicians on Broadway’s 53rd Street with his Clef Club, the noted Afro-Boricua historian Arturo Alfonso Schomburg2 dug up his roots from his San Juan Hill home after campaigning for the independence of his native Puerto Rico from Spain. Both displaced migrants, they blazed new trails redefining and rediscovering the role and history of Black and Puerto Rican people in America.

After his 1891 New York arrival, Schomburg coined, and I.D.’d himself, “AfroBorinqueño”—a century before the trend caught on for today’s Latinx. Schomburg found work in newsrooms and mailrooms, even becoming a mason. He lived among a thriving community of Black porters, tailors, drivers, dock workers, shopkeepers, publishers, and pool hall workers, harboring all kinds of skills, trades, and talents. From 140 West 62nd Street,3 Schomburg hunted through bookstores, thrift shops, and churches for the history of Black people. He was on a mission to defy the American grade school teacher from his native Puerto Rico who told him Negros had no history. He pieced together an extensive collection that later became the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Meanwhile, he helped build institutions and authored essays. His work was muse for the Harlem Renaissance’s Black literati. As housing advocate Jane Jacobs4 described it, “Impersonal city streets make anonymous people…”. The streets of San Juan Hill were personal.

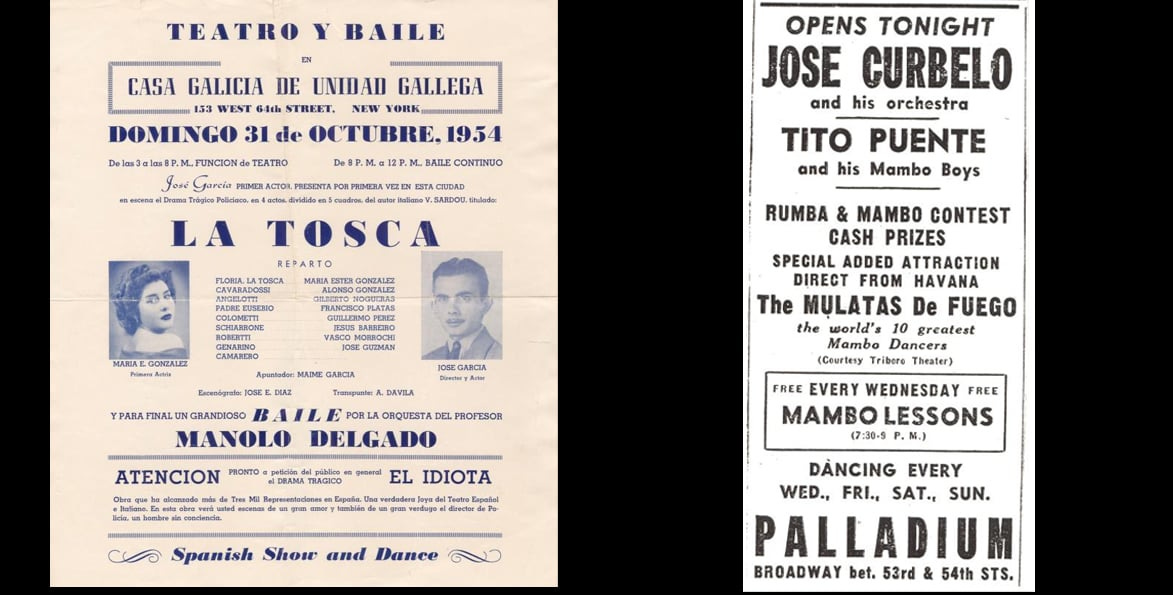

From monotonous rows of tenement housing teeming with immigrant boarders, migrants, and transients looking for a better life, San Juan Hill's resident bandleader James Reese Europe conjured an enterprising spirit of empowerment and advocacy with his musician's guild. His 1912 Carnegie Hall debut showcased 125 of the best all-Black musicians. Ignored by the American Federation of Musicians (AFM), his successful Clef Club drew $120,000 yearly in artist fees: over $3 million today. Black writers and actors performed at the 63rd Street Music Hall. Dark, smoky basement bars pressed against the Templo Masonico Hispanoamericana in 1913. Crowds packed Jungle's Casino to hear stride piano pioneer James P. Johnson's hit "Charleston." By the 1940s, the neighborhood became a popular arena for Latin music dances—from the St. Nicholas Arena on West 66th to the Palladium Ballroom on Broadway and 53rd Street; the Chateau Madrid on West 58th Street, and, of course, the famous Copacabana on 60th and Central Park West. A music explosion brewed.

Their music reflected the politics of colonialism: the selling of the farmlands; the work in factories; the cold concrete streets pounded by hard hearts from marauding gangs; the benefits of Home Relief and the language struggles.

With the onset of World War I, Lieutenant James Reese Europe organized the country's first all-Black orchestra to tour France. He recruited eighteen brass players from Puerto Rico, the island that Europe described as "a musical mecca."5 Known as the Harlem Hell Fighters, the 369th U.S. Infantry Regiment, was welcomed home from war with a parade in 1919. James Reese Europe became a household name. The Afro-Boricua musicians remained in New York, including the trombonist Rafael Hernandez.6 Latino musicians arriving on these shores knew to go to East Harlem first, the place where Hernandez opened the first Latin music record store in New York City in 1927. Located on 114th Street, the store was a breeding ground for players that became a resource for bandleaders, record label owners, and anyone else in need of musicians—in San Juan Hill and other parts of the city.

By the late 1920s, Rafael Hernandez and his Trio Borinquen performed at Spanish restaurants around San Juan Hill as well as the Spanish Sundays at the Apollo Theater in Harlem. Hernandez's early "rhumba fox" recordings stamped him a pioneering jazz trendsetter, as were the many Puerto Rican and Cuban musicians arriving on these shores. Afro-Cubano Alberto Socarras, who lived in a brownstone off Central Park West, is credited with the earliest known 1927 jazz flute solo on Clarence Williams' "Shooting the Pistol" recording.

By the 1930s, the Latino community of San Juan Hill, like the music, grew. Puerto Rican composers Pedro Flores and Manuel Jimenez (“El Canario") were popular exponents of plena, boleros, son-montuno, gurachas, aguilnaldos, danzas, and paso dobles. Their music reflected the politics of colonialism: the selling of the farmlands; the work in factories; the cold concrete streets pounded by hard hearts from marauding gangs; the benefits of Home Relief and the language struggles.

From the doors of Pueblo Español's fiesta dance in the grand ballroom of Centro Galicia on Columbus Avenue at 66th Street, the distinct recorded baritone of the world's most exquisite interpreter of tango, Carlos Gardel, wafted. Later, Libertad Lamarque performed there, as well. These were world renowned Latin music artists whose songs were celebrated from the streets of San Juan Hill. Meanwhile, the Afro-Cuban “Peanut Vendor” was heard from every restaurant as Latin music lessons, recitals, and dances began to take hold in the area.

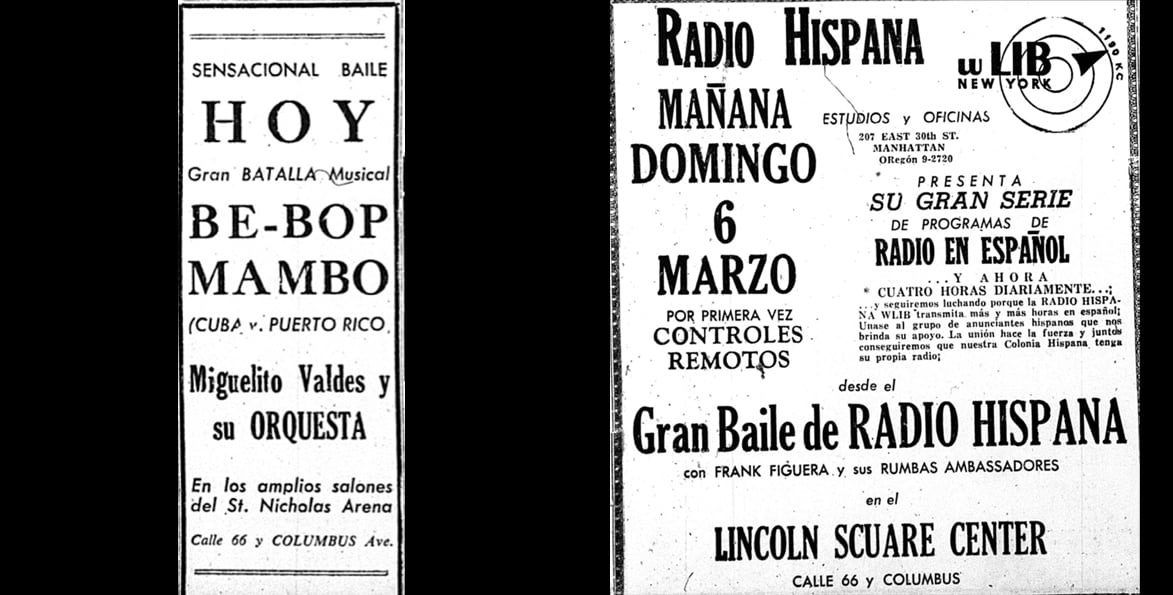

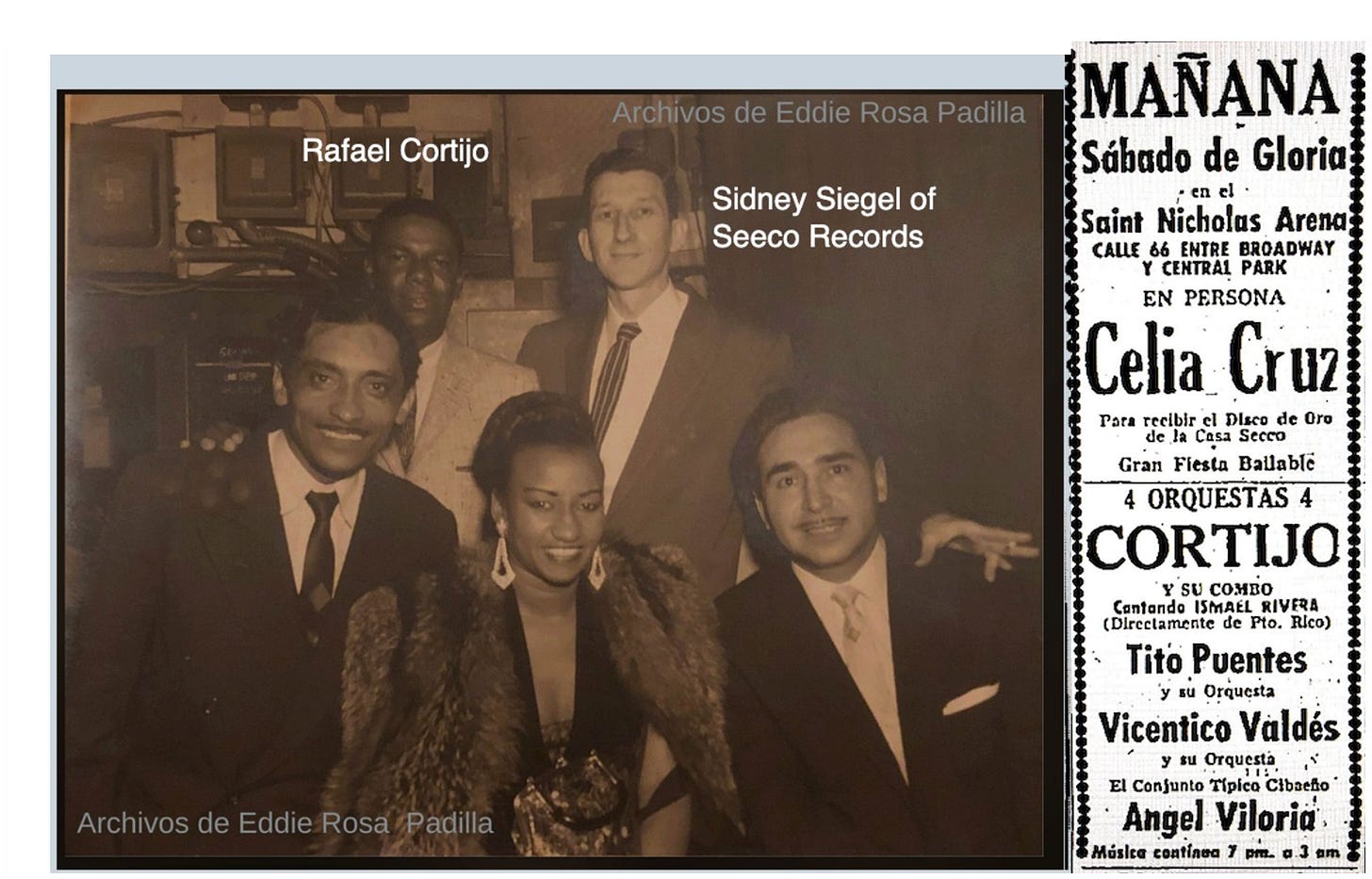

By the 1940s, two venues that sat across from each other on West 66th Street became the center of Latin music concerts and dances in San Juan Hill. A former ice skating rink, the St. Nicholas Arena, and a multi-purpose hall, Lincoln Square Center, became fierce competitors for Latino music lovers. Regular boxing events had attracted many to the St. Nicholas Arena, a 4,000-seater where Black and Puerto Rican spectators watched Kid Chocolate and Rocky Graziano fights, as well as Muhammad Ali's last technical knockout. After World War II, the venue also hosted Latin music orchestras, dances, and jazz concerts. While Xavier Cugat played a steady beat at the Waldorf between Hollywood films, his singer Miguelito Valdes (whose "Babalu" Desi Arnaz covered on I Love Lucy) was advertised as a contender in a musical battle between bebop and mambo on March 5, 1949 at the Arena. Meanwhile, the “Lincoln Scuare (sic) Center,” as it was known in Spanish language ads, became the site of many mambo nights and fundraisers. Bandleader Alberto Iznaga, the Happy Boys, Miguelito Valdez, Bobby Capó, Diosa Costello, Machito & His Afro-Cubans, and Al Santiago’s Cha-Ka-Nu-Nu Boys were among the many performers at the Center.

By the second wave of migration from Puerto Rico, Boricuas gravitated to San Juan Hill, the area where word of mouth said: The West Side is the best side.

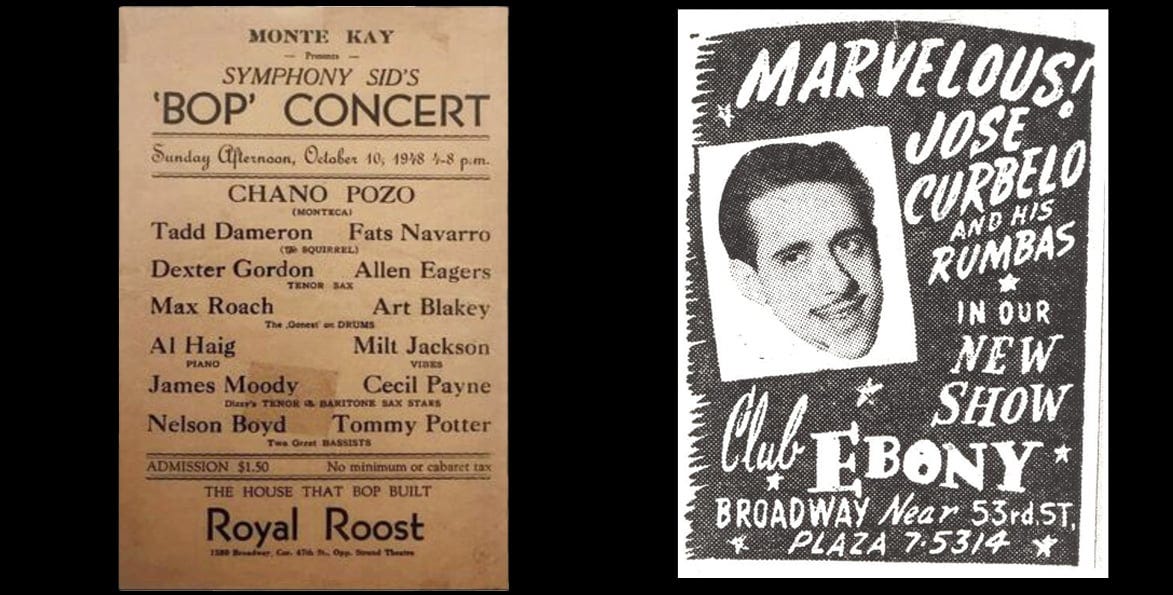

Meanwhile, the music that reverberated through San Juan Hill was becoming popular across the country. The 1940 AFM strike flooded U.S. radio airwaves with free Latin music. The record business boomed. Thelonious Monk, Cab Calloway, and Dizzy Gillespie were only a few of the many to embrace bebop and swing. Disney released: The Three Caballeros. Hollywood-issued "rhumba-themed" movies followed. Mexican films lassoed New York movie houses as the garment industry grew in America. Carmen Miranda became a household name. The 1940s and 50s’ rhumba, mambo, and merengue craze blazed through American dance schools and ballrooms: the Stork Club, Latin Quarter, Morocco, and the Copacabana. Hollywood images of gangsters dancing rhumba glared from movie screens. Latin dance music rang from radio programs, television sets, and speakers from ballparks to fight rings. 1948 saw another musician's strike that placed Tito Puente's "Abaniquito" at the top of America's national hit parade. And who can forget the legendary smoky radio voice of jazz DJ Symphony Sid, who not only popularized bebop but also produced a "Bop Concert" at the Royal Roost featuring Chano Pozo on the same bill with Dexter Gordon, Fats Navarro, Max Roach, Art Blakey, and many more a stone's throw away from San Juan Hill?

By the late fifties, the music of Chilean crooner Lucho Gatica competed with the Spanish child prodigy Joselito (later featured on the Ed Sullivan Show) and the Mexican Toña La Negra from El Cano Restaurant & Bar at 102 W. 64th Street. The iconic Arsenio Rodríguez,7 who changed the face of Latin music by adding the outlawed conga to the Latin music line-up, immortalized San Juan Hill with his classic tune, “Fuego en la 23.” The theme about a fire at his rooming house located “En el 23 West de la sixty-fifth" is sung very clearly in English at the top of this number. Although Latin music's queen, Celia Cruz, made her New York debut from the stage of the St. Nicholas Arena in 1957, her book erroneously places the iconic site in the Bronx!

During the first half of the 20th century, San Juan Hill was a musical powerhouse. Jazzers welcomed congas into the mix. Funky back beats created an explosive mambo and jazz music scene across the city and beyond. But while the music played, political forces simmered. A shift took shape in the neighborhood.

Politics led the way

During the 1930s, San Juan Hill's Puerto Rican community grew alongside other Latino enclaves, notably East Harlem whose residents increased to more than 40,000.8 As political turmoil from the 1935 Harlem Race Riots united East and West Harlem, its Socialist Congressman, Vito Marcantonio, stood behind the Puerto Rican freedom fighters protesting colonialism. As he organized, educated, and unified the communities, East Harlem was eyed for demolition, designated a slum, and targeted by the City’s most powerful, unelected builder: Robert Moses.9

Political issues became front-page news for Spanish language newspapers. Masons, labor organizations, and activists held fundraising dances.10 Rent parties with live musicians were common occurrences as corporations placed ads in Puerto Rico for cheap labor and a free month's lease in New York. Many moved around. The ones who could went to the West Side, including the San Juan Hill neighborhood. One example includes Cuban bandleader and Latin Jazz interpreter Alberto Iznaga who composed "Going Conga" for Cab Calloway. He lived in what was described as a "plush Central Park West apartment”11 when the FBI inquired about his draft notice in 1943. After searching three years in East Harlem, they found him in San Juan Hill.12

As Jazz topped the hit parade while America did a "conga line" with Latin music, the City's builder, Robert Moses, mowed down Black and Puerto Rican communities like an army. He blasted through blocks, tore up streets, and demolished schools, theaters, social clubs, institutions, churches, and basement bars.13 By 1949, the City aggressively rolled out its version of the Title I: Urban Renewal Program directed by Robert Moses,14 the same head of the government-funded Slum Clearance Program that declared East Harlem a ghetto and, through eminent domain, gutted more than fifty city blocks of tenements, stores, and industrial buildings on its southern half, displacing thousands.

Moses next set his sights on San Juan Hill. Construction began in 1959 after Moses' Committee deemed the area, "New York's Worst Slum." Again, Moses steered a gravy train everyone wanted a seat on.15 The $185 million, 14-block, 48-acre Lincoln Square Project replaced an irregular tract of tenements and warehouses northwest of Columbus Circle between 60th and 70th Streets. With Nelson R. Rockefeller III heading its moneyed board, they represented New York's WASP leadership joined by major white Jewish and Catholic ethnic communities; theirs was an elite, semi-democratic slant, familiar with how federal government works—and unapologetically male.

Moses added the Lincoln Square Towers. Next, he made room for Fordham University and the New York Philharmonic to reside alongside the Met Opera House. Finally, through the new Title I: Urban Renewal Program, Moses yanked six prime acres of real estate adjacent to Lincoln Center and gifted them to the University, so grateful they named a central square of their Lincoln Center campus Robert Moses Plaza.

The public outrage moved Mayor Wagner to organize a citizen's committee through the Urban Renewal Board (URB).16 Although well-intentioned, it brought in brownstone owners that opened the gates to the real estate industry's hold today.

But a new wave of Latino activism was sparked. And it was heralded by the many drummers draping the streets with their interactive beats. "Watermelon Man," "El Pito," and "I Like it Like That" boogalooed onto the airwaves and protest lines. Mongo Santamaria's 1963 "Afro Blue" mixed African scales with jazz and Cuban beats. Ray Barretto's "Watusi" was at the top of Cousin Brucie's hit parade. One of the last jazz and Latin music holdouts from San Juan Hill, Sweet Waters, remained to host Latin music and jazz acts into the ‘70s.

Conga drummers led a long line of marchers and anti-poverty advocates through the streets. "The block is being broken down," sang the popular cultural duo Pepe & Flora. Suddenly, marchers realized the nine sealed buildings designed for demolition along their route were in good condition. The City made promises. The community would now hold them to it. With the anguish of dislocation seriously affecting the Upper West Side, Operation Move-In blossomed.

From this initiative El Comité arose. As a direct result of the Lincoln Square displacements, a septet of concerned community members—including the author of Radical Humanity, Rose Muzio—became squatters, "liberating" an abandoned storefront at 577 Columbus Avenue to meet the challenge before them. El Comité became a leading force within Operation Move-In. The documentary Break and Enter (Rompiendo Puertas) bears witness to the city administration's rage that threatened squatters with forced eviction as it sent squads of janitorial "goons" to unoccupied buildings to wreck electrical wiring, break fixtures, remove stoves, refrigerators, and sinks. Squatters refused to leave. All is caught on film to the soundtrack of salsa music beats.

In a short time, El Comité helped 190 families stay in 38 buildings rent-free as they tried to negotiate with city officials. A food coop, school, newspaper, and maintenance work were communal. They managed to do what leaders like Herman Badillo, Ramon Velez, or Amalia Betances could not, owing to their ties with real estate developers involved in what the people called "urban removal." By 1970, one-third of the Island's Boricuas—one million Puerto Ricans —lived in New York City scattered across East Harlem, Harlem, the Upper West Side, and the Bronx (just as the borough was being abandoned by landlords and set on fire).

Meanwhile, the music that had thrived in San Juan Hill played on. Eddie Palmieri made them dance for “Justicia.” Ray Barretto called for unity with "Together.” The Chez José nightclub featured two Latin music bands weekly on 77th Street and Central Park West. LP covers screamed: “Protesta.” The Motown sound created sonic waves over transistor radios as club DJs played Latin and soul.

Conclusion

Jane Jacobs observed, "Unstudied, un-respected cities have served as sacrificial victims.”17 The Lincoln Square Development Project laid bare the brunt jolt urban renewal can wallop. It stained the government's credibility and the political elites it hired to "appease" its people. Comité organizer Manuel Ortiz noted: "The struggle against urban renewal was never going to be won. But it created an urgent need for community education and long-term organizing."

New York's shining metropolis is unrecognizable from the turn of the last century. Economical housing is scarcer than ever. Activists demanded 30% affordable housing from all new construction.18 19 It never happened. What did happen was the entry of real estate developers into the equation. Today’s luxury towers gleefully announce a "lottery" where a handful of apartments are consigned "affordable," though their cost-effectiveness is debatable.

After one hundred years, communities that transitioned from the agricultural to the industrial age are now faced with extinction in this century's economic age. Clearly, Gotham's creative, working-class communities have been sacrificed for a profitable future. Yet, every Sunday afternoon since the fifties, on Central Park's west side by the 72nd Street fountain, teams of congüeros gather in the forest of the City's metropolis to drum out the beats of their African ancestors. The music left behind continues to mark the footprints of their creators and the collaborations forged by dint of mutual territory, respect, and a dance of creative energy and influence felt from the roots, routes, and rhythms of San Juan Hill.

Read my Citations on the Legacies of San Juan Hill Site.

Here’s an interesting panel discussion where I, along with several colleagues, explore the early venues of the 1900s that showcased classical Latin music. We also discuss Rafael Hernández's role in popularizing the music for the growing Boricua, Cuban and Dominican communities. Additionally, we touch on how Americans traveling to Cuba during Prohibition discovered this music, poorly translated Moisés Simons’ El Manicero better known as "The Peanut Vendor," and turned it into a national phenomenon in the United States.

Lincoln Center Panel Discussion on Puertorican Music of the 20th Century